Imaginary unit

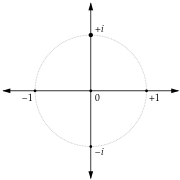

In mathematics, the imaginary unit allows the real number system  to be extended to the complex number system

to be extended to the complex number system  , which in turn provides at least one zero for every polynomial P(x) (see algebraic closure and fundamental theorem of algebra). The imaginary unit is denoted by i, j, or the Greek ι (see alternative notations). Although its precise definition varies, the imaginary unit's core property is that i2 = −1.

, which in turn provides at least one zero for every polynomial P(x) (see algebraic closure and fundamental theorem of algebra). The imaginary unit is denoted by i, j, or the Greek ι (see alternative notations). Although its precise definition varies, the imaginary unit's core property is that i2 = −1.

There are in fact two square roots of −1, namely i and −i, just as there are two square roots of every non-zero real number. Misuse of the imaginary unit can lead to difficulties.

For a history of the imaginary unit, see Complex number: History.

Contents |

Definition

(repeats the pattern from blue area) (repeats the pattern from blue area) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(repeats the pattern from blue area) (repeats the pattern from blue area) |

The imaginary number i is defined solely by the property that its square is −1:

Or, equivalently:

If i is defined in this way and it is assumed that it can be manipulated as if it were an unknown ("imagined") variable, then it follows from straightforward algebra that the second solution to the above quadratic equations is −i.

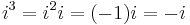

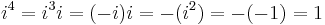

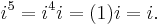

Although the construction is called "imaginary", and although the concept of an imaginary number may be intuitively more difficult to grasp than that of a real number, the construction is perfectly valid from a mathematical standpoint. Real number operations can be extended to imaginary and complex numbers by treating i as an unknown quantity while manipulating an expression, and then using the definition to replace any occurrence of i2 with −1. Higher integral powers of i can also be replaced with −i, 1, i, or −1:

i and −i

Being a quadratic polynomial with no multiple root, the defining equation x2 = −1 has two distinct solutions, which are equally valid and which happen to be additive and multiplicative inverses of each other. More precisely, once a solution i of the equation has been fixed, the value −i (which, one can prove algebraically, is not equal to i) is also a solution. Since the equation is the only definition of i, it appears that the definition is ambiguous (more precisely, not well-defined). However, no ambiguity results as long as one of the solutions is chosen and fixed as the "positive i". This is because, although −i and i are not quantitatively equivalent (they are negatives of each other), there is no algebraic difference between i and −i. Both imaginary numbers have equal claim to being the number whose square is −1. If all mathematical textbooks and published literature referring to imaginary or complex numbers were rewritten with −i replacing every occurrence of +i (and therefore every occurrence of −i replaced by −(−i) = +i), all facts and theorems would continue to be equivalently valid. The distinction between the two roots x of x2 + 1 = 0 with one of them as "positive" is purely a notational relic; neither root can be said to be more primary or fundamental than the other.

The issue can be a subtle one. The most precise explanation is to say that although the complex field, defined as R[X]/ (X2 + 1), (see complex number) is unique up to isomorphism, it is not unique up to a unique isomorphism — there are exactly 2 field automorphisms of R[X]/ (X2 + 1), the identity and the automorphism sending X to −X. (These are not the only field automorphisms of C, but are the only field automorphisms of C which keep each real number fixed.) See complex number, complex conjugation, field automorphism, and Galois group.

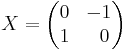

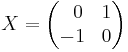

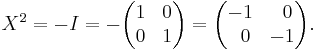

A similar issue arises if the complex numbers are interpreted as 2 × 2 real matrices (see matrix representation of complex numbers), because then both

and

and

are solutions to the matrix equation

In this case, the ambiguity results from the geometric choice of which "direction" around the unit circle is "positive" rotation. A more precise explanation is to say that the automorphism group of the special orthogonal group SO (2, R) has exactly 2 elements — the identity and the automorphism which exchanges "CW" (clockwise) and "CCW" (counter-clockwise) rotations. See orthogonal group.

All these ambiguities can be solved by adopting a more rigorous definition of complex number, and explicitly choosing one of the solutions to the equation to be the imaginary unit. For example, the ordered pair (0, 1), in the usual construction of the complex numbers with two-dimensional vectors.

Proper use

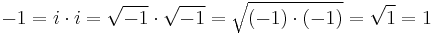

The imaginary unit is sometimes written  in advanced mathematics contexts (as well as in less advanced popular texts). However, great care needs to be taken when manipulating formulas involving radicals. The notation is reserved either for the principal square root function, which is only defined for real x ≥ 0, or for the principal branch of the complex square root function. Attempting to apply the calculation rules of the principal (real) square root function to manipulate the principal branch of the complex square root function will produce false results:

in advanced mathematics contexts (as well as in less advanced popular texts). However, great care needs to be taken when manipulating formulas involving radicals. The notation is reserved either for the principal square root function, which is only defined for real x ≥ 0, or for the principal branch of the complex square root function. Attempting to apply the calculation rules of the principal (real) square root function to manipulate the principal branch of the complex square root function will produce false results:

(incorrect).

(incorrect).

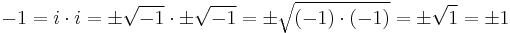

Attempting to correct the calculation by specifying both the positive and negative roots only produces ambiguous results:

(ambiguous).

(ambiguous).

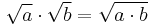

The calculation rule

is only valid for real, non-negative values of  and

and  .

.

These problems are avoided by writing and manipulating  , rather than expressions like

, rather than expressions like  . For a more thorough discussion, see Square root and Branch point.

. For a more thorough discussion, see Square root and Branch point.

Properties

Square root

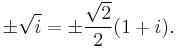

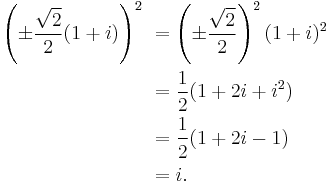

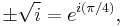

The square root of i can be expressed as either of two complex numbers[1]

Indeed, squaring the right-hand side gives

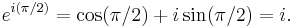

The result can be derived with Euler's formula

by substituting x = π/2, giving

Taking the square root of both sides gives

which, through application of Euler's formula to x = π/4, gives

Multiplication and division

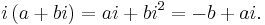

Multiplying a complex number by i gives:

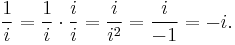

Dividing by i implies the reciprocal of i:

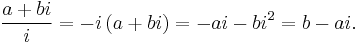

Using this identity to generalize division by i to all complex numbers gives:

Powers

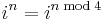

The powers of i repeat in a cycle expressible with the following pattern, where n is any integer:

This leads to the conclusion that

where mod 4 represents arithmetic modulo 4.

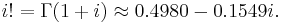

Factorial

The factorial of the imaginary unit i is most often given in terms of the gamma function evaluated at 1+i:

Other operations

Many mathematical operations that can be carried out with real numbers can also be carried out with i, such as exponentiation, roots, logarithms, and trigonometric functions.

A number raised to the ni power is:

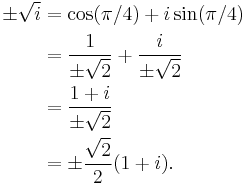

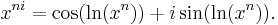

The nith root of a number is:

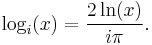

The imaginary-base logarithm of a number is:

As with any complex logarithm, the log base i is not uniquely defined.

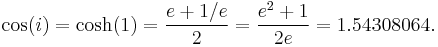

The cosine of i is a real number:

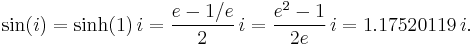

And the sine of i is imaginary:

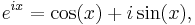

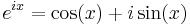

Euler's formula

where x is a real number. The formula can also be analytically extended for complex x.

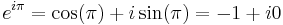

Substituting x = π yields

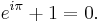

and one arrives at Euler's identity:

Euler's identity is noted for its elegance, in that it relates five of the most significant mathematical quantities under three of the most basic operations.

Example

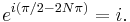

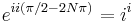

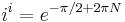

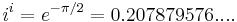

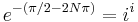

Substitution of x = π/2 − 2πN, where N is an arbitrary integer, produces

Or, raising each side to the power i,

or

,

,

which shows that ii has an infinite number of elements in the form of

where N is any integer. This value is real, but it is not uniquely determined, since the complex logarithm is a multivalued function.

Taking N = 0 provides the principal value

Alternative notations

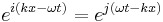

- In electrical engineering and related fields, the imaginary unit is often denoted by j to avoid confusion with electrical current as a function of time, traditionally denoted by i(t) or just i. The Python programming language also uses j to denote the imaginary unit. MATLAB associates both i and j with the imaginary unit.

- Some sources define j = −i, in particular with regard to travelling waves (e.g. a right travelling plane wave in the x direction

).

). - Some texts use the Greek letter iota ( ι ) for the imaginary unit, to avoid confusion. See Biquaternion.

See also

Notes

- ↑ To find such a number, one can solve the equation (x + iy)2 = i x2 + 2ixy − y2 = i Because the real and imaginary parts are always separate, we regroup the terms: x2 − y2 + 2ixy = 0 + i and get a system of two equations: x2 − y2 = 0 2xy = 1 Substituting y = 1/2x into the first equation, we get x2 − 1/4x2 = 0 x2 = 1/4x2 4x4 = 1 Because x is a real number, this equation has two real solutions for x: x = 0.51/2 and x = −0.51/2. Substituting both of these results into the equation 2xy = 1 in turn, we will get the same results for y. Thus, the square root of i is the number 0.51/2 + i0.51/2 and −0.51/2 − i0.51/2. University of Toronto Mathematics Network: What is the square root of i? URL retrieved March 26, 2007.

References

- Paul J. Nahin, An Imaginary Tale, The Story of √−1, Princeton University Press, 1998

![\!\ \sqrt[ni]{x} = \cos(\ln(\sqrt[n]{x})) - i \sin(\ln(\sqrt[n]{x})).](/I/a0fbe6b07abd5861871b5f8af81f82a4.png)